BEAUTY of music | jazz arrangements

Jazz Arrangements: not the story but how the story is told

Brent Wallarab is a trombonist, co-founder of the Buselli-Wallarab Jazz Orchestra, professor of music at Indiana University's Jacobs School of music and a leading authority on historical composition for jazz orchestras. In this month's Beauty of Music, he discusses the craft of jazz arranging.

What is a musical arrangement and how does it differ from a composition? The simple answer is that a composition is a piece of music where all portions (melody, harmony, orchestration, etc.) are original creations of the composer while an arrangement utilizes a pre-existing musical idea, usually a melody, which is then “rearranged” into an entirely different work from its original incarnation. In a musical arrangement, a pre-existing melody, “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” for example, can be transformed as other musical elements are changed. In fact, Mozart did this very thing with the aforementioned tune, running it through 12 variations, utilizing many different compositional techniques [we wrote about classical music variations in a prior post]. Harmony may be altered, from as simple a technique as changing it from major to minor, to a fully re-harmonized texture with every note being given a different complex chord. The rhythm may be changed, for example changing the meter from four beats to the measure to three beats to the measure. The tempo can be moved from fast to slow, the style can be changed from a march to a Rhumba, and a solo piano score can be fleshed out to be played by a 60-piece orchestra. When an arranger transforms a pre-existing musical idea to become something else, all of the techniques of composition may be employed to “re-write” the original piece. “Why is this even necessary?” one may ask. If the original work were a perfect piece of art on its own, why would an arranger choose to transform it? Let’s compare the art form of arranging to other artistic disciplines.

In transforming a pre-existing work of art into something else, the goal is not to improve upon it. By reinterpreting a pre-existing idea, the artist allows the observer to view the original material through different perspectives, often illuminating aspects of the subject material not present in its original incarnation. Portrait and still life painting had been around for centuries before Picasso, but in applying the concepts of Cubism, Picasso gives the viewers a new way of looking at the human form or a collection of inanimate objects by rearranging aspects of the subjects. Japanese filmmaker Akria Kurosawa retold many of Shakespeare’s most beloved plays as Samurai tales, contextualizing the insights of Shakespeare into an historical perspective more relevant to Japanese culture. Neither Picasso nor Kurosawa considered their work improvements over their inspirations, but rather sought to channel their voice, their vision, and their perspective through them. This is what an arranger does with music.

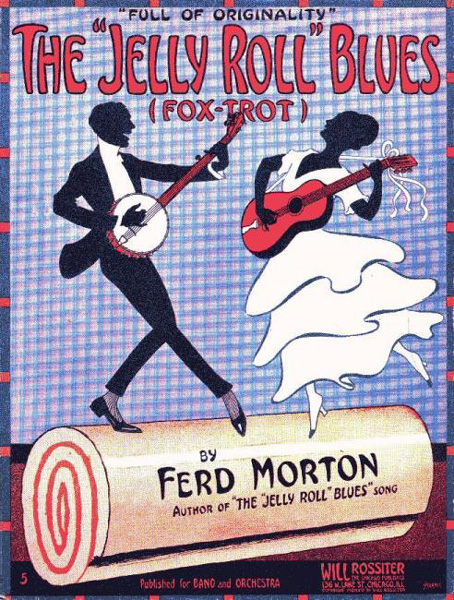

There have been arrangers in jazz from the very beginning. The earliest small jazz groups in New Orleans around the start of the last century were blending the rhythms of ragtime, the blues of rural Americans, and the forms of Sousa’s marches on the spot, rearranging their source material to meet the expectations of their employers who craved a variety of music. It wasn’t much later that Jelly Roll Morton started writing this down on manuscript paper, understanding that the rhythmic and expressive elements of jazz did not have to be purely improvisational. Soon thereafter, jazz-influenced dance bands started to become bigger, making it necessary for writers to arrange the music. Large numbers of musicians improvising would create cacophony, disorder, and tonal chaos, so it had to be organized.

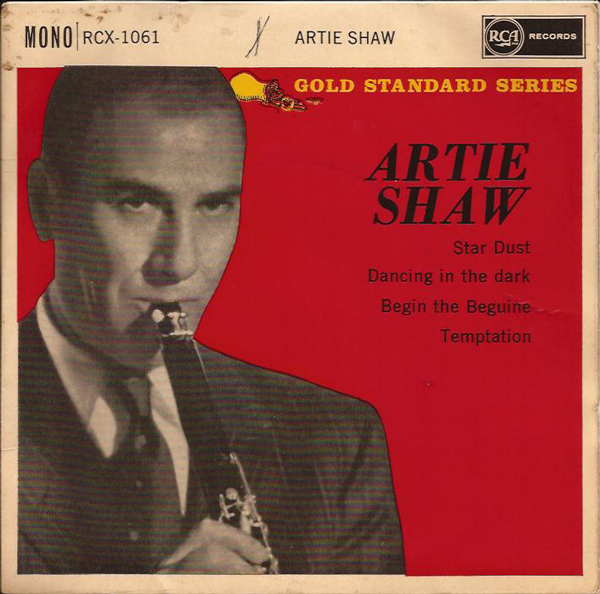

While many important original jazz compositions developed during this time, most of the work involved arranging popular tunes. Jazz-based dance band music was the most popular music in America from the mid-30’s arguably through the mid 50’s when Elvis Presley cemented rock n’ roll as the dominant force in pop music. For the dance bands to succeed, they were compelled to present every new pop tune as it rose in the charts, their dancers and listeners expecting to hear the newest tunes on the hit parade. Fiercely competing with one another for employment, record sales, and fame, the bands had to play the same songs, but needed to stand apart from one another. To develop a unique sound and style, it fell upon the staff arrangers to imaginatively package them in a style instantly associated with the bandleader. While commerce may have been the prime inspiration, the result was a quickly developing art form of astonishing depth, sophistication, and nuance. The classic standard “Stardust” by Hoagy Carmichael was so popular that there were hundreds of different arrangements. I recommend listening to "Stardust" as recorded by Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw, and Tommy Dorsey, all the same recognizable song yet so beautifully contrasting in interpretation.

The craft of jazz arranging is now universally accepted worldwide as a serious art form, and it is due to the vision of Joel Harrison, artistic director of the American Pianists Association, that this element has become a mainstay in the American Pianists Awards. The parallel to classical piano is obvious in that the finalists are featured in settings from solo piano to solo voice within an orchestra texture. The same opportunities exist in a jazz setting but the competition has added a unique element that has never been done before. Rather than acquiring previously written big band arrangements that feature the piano prominently, the Association commissions new works to be written for each finalist. Not only does this allow the work to be crafted to fit the musical temperament of each pianist, it also advances the art form by creating new works for each new cycle of the competition.

As arranger for the American Pianists Awards, it falls upon me to craft the new arrangements for each finalist. Rather than simply write a new work for jazz piano with jazz orchestra, I work hand-in-hand with each finalist, crafting the piece to his or her specifications. In jazz, each artist develops their own subtle vocabulary that sets them apart from everyone else. Before I begin writing, I transcribe (essentially taking musical dictation, writing down what I hear on the recording) improvisations of the pianist to get a feel for their unique voice. I then incorporate these elements into the written portion of the arrangement, which allows for seamless continuity from solo piano to ensemble. This process guarantees that each piece on the program not only fits the soloist like a well-tailored suit, but also provides contrast on the program.

Sullivan Fortner with Buselli-Wallarab Jazz Orchestra performing Brent Wallarab's arrangement of "I Mean You" by Thelonious Monk at the 2015 American Pianists Awards.

Art is the re-imagining, re-constructing, and re-telling of the human experience. It’s not the story, but how the story is told. When a jazz pianist or jazz arranger reinvents a beautiful tune like “Nature Boy” it becomes a personal statement on the theme, transformed harmonically, texturally, and rhythmically to tell the story of the artist. The source material is the common thing we all share, but how we experience it and express it as individuals is what makes it unique and precious.

---

Brent Wallarab and the Buselli–Wallarab Jazz Orchestra will return as collaborative artists for the 2019 American Pianists Awards. Subscribe to our newsletter to follow progress towards this next competition for jazz pianists and read other articles about the beauty of music.