BEAUTY of music | Variations

American Pianists Awards finalist Sam Hong will play three sets of variations in his Premiere Series concert December 4. APA Artistic Administrator Milner Fuller explores this shifting style in this month's Beauty of Music.

Variation form is possibly as old as music itself. One can imagine musicians playing at a dance. In order to fill more time, rather than play new tunes, they can just play the same tunes, but change things up each time, often becoming more elaborate with each reiteration. Voila! Theme and variations!

Variations evolved into a more codified form beginning in the 16th century. The keyboard has long been the most popular instrument for theme and variations. The form reached unprecedented length and complexity with Bach’s Goldberg Variations in 1741.

Variations can fit into many different kinds of groups. The one most familiar to us, theme and variations, was quite popular in the 18th century. In this form, a theme is stated in its most simple form (often a chorale-like texture), and it is followed by a set of variations of the same length. Often, the theme consists of 2 repeated sections, and the second section can be longer than the first. The variations then are the same number of bars as the theme. The theme could be original, or it may come from a different work either by the composer or even someone else.

Theme and variations can be a stand-alone work, usually for keyboard, or part of a larger multi-movement work, like a sonata, string quartet, or even a concerto or symphony. There are many popular examples. The theme from the second movement of Haydn’s Op. 76 No. 3 quartet would later become the German national anthem. Mozart wrote a witty set of variations on “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.” Schubert would use themes from some of his lieder as the basis for variations in two of his best-known chamber works: the “Trout” Quintet and the “Death and the Maiden” Quartet. Both nicknames come from the song from which the theme comes, “Die Forelle” and “Der Tod und das Mädchen.” If, like me, you own a Samsung washer and dryer, you hear the “Trout” theme chimed when your laundry is dry.

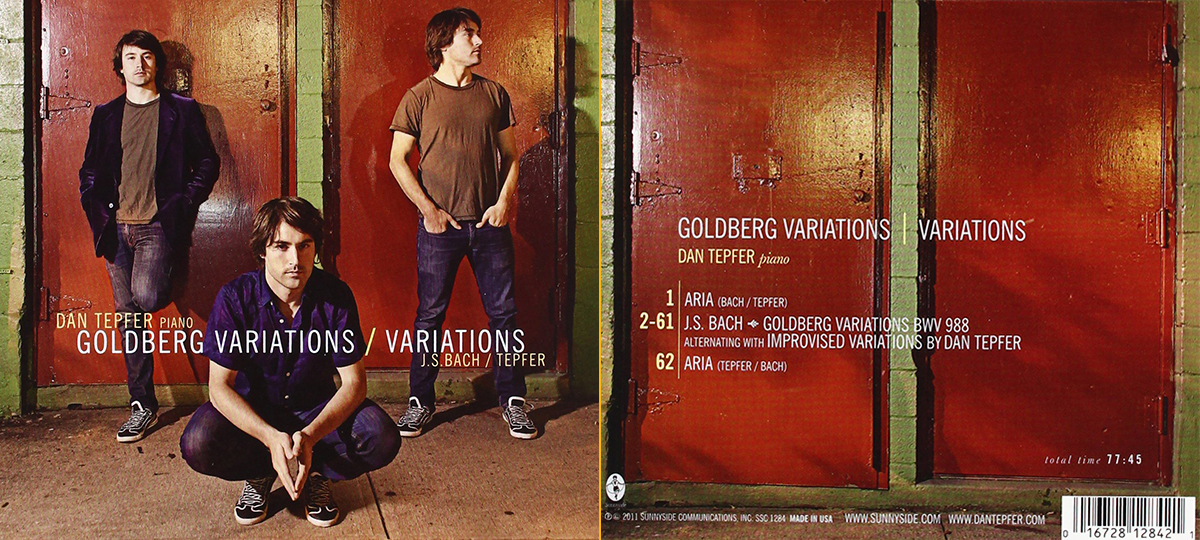

Given its restraints and repetitive nature, composers used theme and variations to show off their cleverness. Each variation has a distinct character, and the farther the character is from the original setting the better. Bach’s Goldberg Variations and Beethoven’s 33 Variations on a Waltz by Anton Diabelli, Op. 120, both massive works, are almost encyclopedic in their handling of the material. Nearly every conceivable period style is represented somewhere in these works. 2007 American Pianists Awards winner Dan Tepfer has a unique take on the Goldberg Variations. He follows each of Bach’s variations with his own improvised jazz variation based on Bach’s original. Very meta. He has recorded his variations on the Sunnyside label.

On December 4, Sam Hong will perform three sets of variations: Beethoven’s Seven Variations on “God Save the King," WoO 78; Brahms’ Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Op. 24; and Copland’s Piano Variations. Beethoven’s is the most traditional of these pieces. The familiar theme, consisting of a repeated 6-bar phrase followed by a repeated 8-bar phrase, is treated to seven different variations, each of a different character. The theme can be clearly heard in each variation. At the end of the seventh variation, though, Beethoven can no longer be shackled by the limits of the form and unleashes a 37-bar coda that treats the tune more freely.

Brahms, perhaps more than any other composer, loved to look backwards and forwards at the same time. His Handel Variations contain a theme, 25 variations, and an enormous fugue. The theme is presented verbatim from its baroque source (Handel’s Keyboard Suite No. 1 in B flat, HWV 434, 3rd movement), and Brahms incorporates various baroque dances and techniques throughout the thoroughly 19th-century variations. Each variation, like the theme, contains two four-bar sections, and the theme is never completely obscured. The closing fugue also conjures the learned style of the 18th century. While Brahms evokes the style of Handel and Bach, the piece is pure Brahms—full of sonorous bass notes, dense textures and counterpoint, two-against-three rhythms, and pianistic virtuosity.

With his Piano Variations, Aaron Copland sought to turn the variations form on its head. It’s an esoteric work, one that very few appreciate at first listening. Sean Chen, who performs the work now, has mentioned hating it at first. It is dissonant, cold, and harsh. Where most sets of variations feature a simple theme with repeats and regular phrasing, Copland’s is just a seven-note motif that Copland repeats and manipulates throughout the work. The piece is widely regarded as Copland’s finest solo piano work.

Sam Hong will perform his Premiere Series recital December 4 at 3:30 PM at the Indiana History Center. He will be joined in the second half by the Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra to perform Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C Minor. Get Tickets!